Protests Then vs. Now

Charlize Woods, Staff Writer

Digital activism has transformed protest organizing from a months-long process to being done in a matter of hours, but there is a question about whether these viral movements can sustain the pressure that won past victories. Where civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin needed three months and 200 organizers to mobilize 250,000 people for the 1963 March on Washington, today's activists can bring and encourage millions through a single viral video, as this was seen when nearly 7 million gathered for the recent No Kings protests. The shift from photocopied flyers and phone trees to social media has fundamentally changed not just how protests happen, but what they can achieve. This raises concerns about whether speed and reach can replace the organized pressure that ended wars and secured civil rights in the earlier decades.

1963

On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 people converged on the National Mall for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (NAACP). While this began as a mass demonstration centered on economic inequalities, its goals expanded to include passage of the Civil Rights Act, full school integration, and a bill prohibiting job discrimination. What made the gathering remarkable was the logistical organization required to bring together a quarter-million people without email, social media, or reliable long-distance phones. Bayard Rustin coordinated a staff of over 200 activists, created an Organizing Manual, held countless meetings, distributed guides, raised funds church by church, coordinated buses and trains, and prepared thousands of meals (National Archives). The march relied on churches, unions, civil rights organizations, and personal contacts through phone calls, letters, and face-to-face trust-building.

1981

Two decades later, activists confronted the escalating nuclear arms race, as President Ronald Reagan's rhetoric and massive weapons buildup sparked the Nuclear Freeze campaign. Its goal was to halt the nuclear arms race, and organizers relied on door-to-door canvassing, community phone banks, local meetings, photocopied flyers, and existing networks like churches, labor groups, and neighborhood associations (University of Washington). This protest grew one conversation and one community at a time, and on June 12, 1982, one million people flooded Central Park, the largest anti-nuclear protest in American history up to that point, with nearly 3 million more protesting across Western Europe the following year (History.com). These numbers reflected months of infrastructure: booking buses, printing signs, coordinating with police, arranging first aid, and building trust strong enough to convince a million people to show up, demonstrating that power came not only from numbers but from sustained commitment.

Modern Day Activism (2020)

When George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, the world witnessed protest organizing at digital speed, as video of his death spread within hours and protests erupted across all 50 states and more than 60 countries (PMC). The movement’s goal was to demand justice and confront systemic racism, and mobilization unfolded through massive digital activity: the BlackLivesMatter hashtag was used 48 million times on Twitter, TikTok reached 12 billion views, and researchers documented millions of Instagram posts amplifying journalists, celebrities, advocates, and activists (NBC News). Digital organizing also relied on encrypted messaging apps, livestreams, and citizen journalism that enabled protests to form in hours rather than months, with no need for manuals or phone trees. This decentralized, leaderless structure allowed rapid response but raised doubts, as earlier movements and a Pew study suggested concerns about staying power, distraction, and whether social media makes people believe they’re creating change without truly doing so.

No Kings Protest (2025)

On October 18, 2025, nearly 7 million people gathered at more than 2,700 events in all 50 states for “No Kings” protests against President Trump’s administration, marking the largest single-day nationwide demonstrations in U.S. history (CNN Politics). The goals centered on outrage at perceived threats to democracy, ICE raids, troop deployments in U.S. cities, and cuts to federal programs, especially health care. Mobilization followed a hybrid model that used digital tools for rapid turnout while keeping enough organizational structure to coordinate thousands of simultaneous, mostly peaceful events (NPR). The progressive No Kings network built digital infrastructure informed by past movements, enabling social-media-speed mobilization with real coordination, but even with 7 million people in the streets, questions remained about whether one day of demonstrations could create sustained political pressure or whether digital ease encourages protests that governments can simply wait out.

"Protests used to be these big organized events that took a lot of time and effort to make people listen and change, but now it’s like they pop up constantly on my Instagram and Facebook. It feels like the whole point has shifted from changing minds to just showing which side you're on because of how politically divided the world is right now. I think protests are needed, I just don’t know if everyone in the world is willing to listen enough to change.” - Billie Jo Woods, Age 50

Comparison and Analysis

The evolution from the 1963 March on Washington to the 2025 No Kings protests reveals a fundamental change in how Americans organize to protest: in 1963, Bayard Rustin needed three months and 200 organizers to bring 250,000 people to Washington, while in 2025 the No Kings network mobilized 7 million people simultaneously across the country, a speed and scale that would have seemed like science fiction to 1960s civil rights leaders. But raw numbers don't tell the whole story, because the 1963 march and the 1980s Nuclear Freeze movement were built on years of relationship-building, door-to-door canvassing, community meetings, and phone banking that created not just crowds but people who would vote, lobby, and keep showing up. This was an infrastructure that helped pass the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and sustained anti-nuclear activism. Modern protests can mobilize massive crowds with incredible speed, but they often struggle to translate that energy into sustained political pressure, as seen in the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, which showed both the power and limitations of digital organizing; hashtags and rapid mobilization can mask the difference between depth and breadth, because millions of tweets or a single march don't necessarily translate into long-term activism. Yet it would be wrong to dismiss modern protest as “clicktivism,” since millions of people physically showed up for No Kings and Black Lives Matter, and digital tools didn’t replace traditional organizing so much as heighten its potential. The real question is whether modern movements can combine the best of both worlds: using digital speed and scale while still preserving the durability of traditional relationship-building. The challenge new activists face is how to harness digital power without losing the person-to-person organizing that actually changed laws and transformed society.

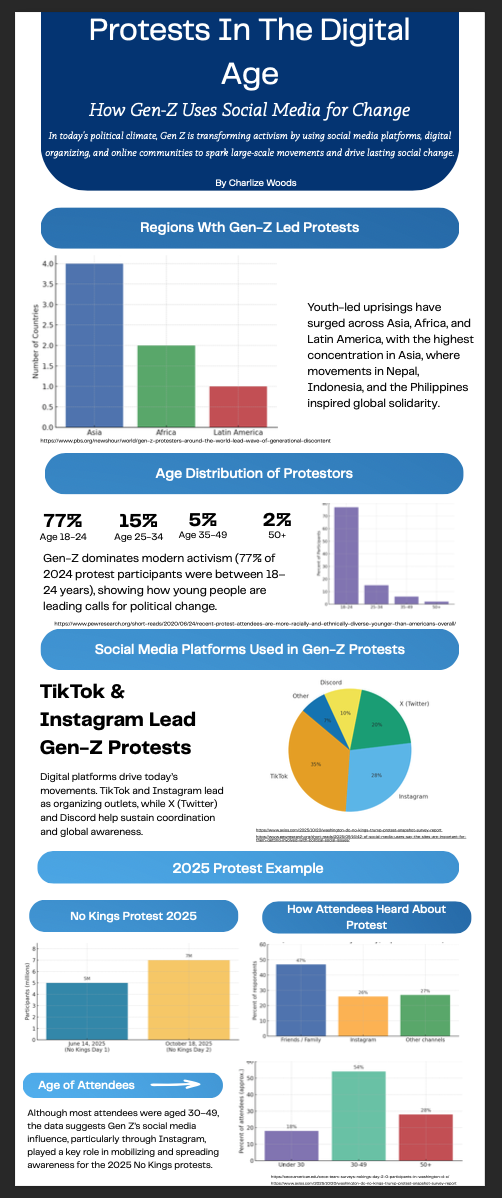

Gen-Z Uses Social Media for Change. Infographic by Charlize Woods