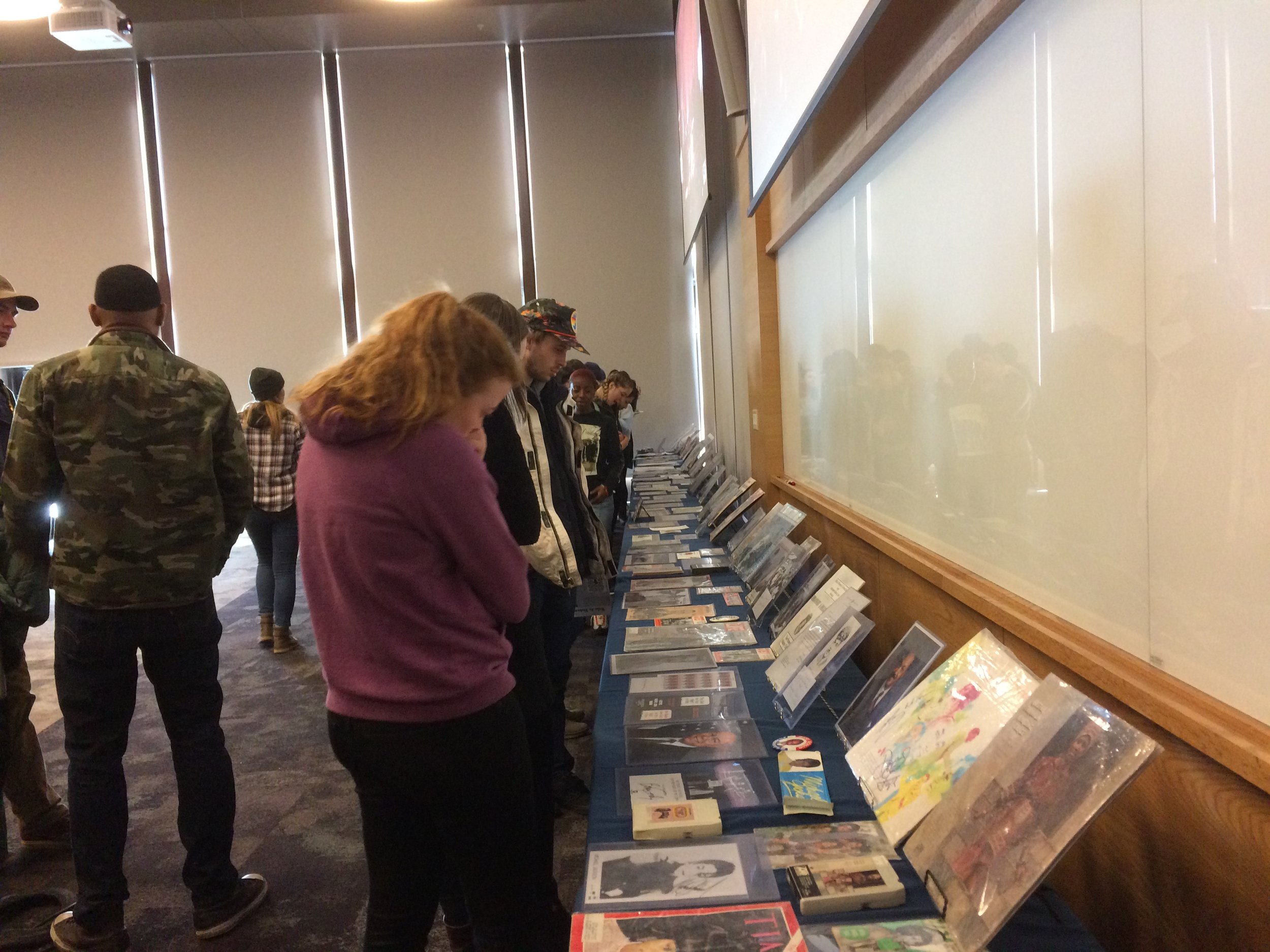

Students observing the Black History 101 Mobile Museum in the Mountain View Room // Allison Upchurch

By: Allison Upchurch, Staff Reporter

Last Monday, February 18, the Office of Diversity and Inclusive Excellence along with the Social Justice and Diversity committee of RUSGA hosted a day-long exhibition in the Mountain View Room of the Black History 101 Mobile Museum. This award-winning mobile museum displayed a selection of the over 7,000 original artifacts of black memorabilia starting from the Trans-Atlantic slave trading era to current hip hop culture.

Some of the artifacts specifically on display on Monday were authentic chains used in the slave trade, original vinyl records of famous speeches by black activists, and signed pictures from famous black performers and athletes.

The collection was founded by Khalid el-Hakim, who has been collecting these artifacts for the last 28 years and decided to go public with his collection after attending the Million Man March on Washington D.C. on October 16, 1995. “I wanted to start sharing this material in public spaces to get us to start thinking about history in a different type of way because we haven’t been taught history honestly,” el-Hakim shared during the lecture portion of the exhibition. “So this was my way of addressing that.”

His lecture, entitled The Truth Hurts: Black History, Honesty, and Healing the Racial Divide, served as an overlook about why the specific artifacts in his collection came to be created and think about how socialization and normalization has caused the racial divide in our country to persist.

“I want to just set a foundation to get us started in thinking about what this all means,” el-Hakim said to introduce his lecture. “It’s a very heavy subject, but I think that we need to be honest about what we see here on display.”

The lecture went into showing how all of the objects on display, as well as other artifacts in his collection but not on display, contribute to the history of separating by race. el-Hakim explained that most of these artifacts were created to create “disconnect” and “disassociation”, especially in objects from the late 1800’s and mid 1900’s that were created to show blacks as inferior or unwelcomed, such as soap advertisements and phrases of speech adopted by the KKK.

Other objects in this collection told a more positive side to this narrative – one of pride and activism that even drew a connection to el-Hakim’s family. He told the story of how he came across a document from 1938 signed by Carter G. Woodson that included a list of supporters for Woodson’s scholarship research in Detroit at that time. “As I am going down this list of patrons listed, I see my grandparents listed,” el-Hakim shared. “That’s a reminder of what the greater work is.”

To learn more about the Black History 101 Mobile Museum, visit their official website or email Khalid el-Hakim at bhistory101@yahoo.com.